Unofficial Translation from The Phnom Penh Post’s Khmer edition

TUESDAY, 2 AUGUST 2016,

TONG SOPRACH

ខ្មែរមិនអាចផ្សះផ្សាគ្នាបាន ដោយសារប្រវត្តិសាស្ត្រមានជម្លោះដណ្ដើមអំណាចគ្នាឯង?

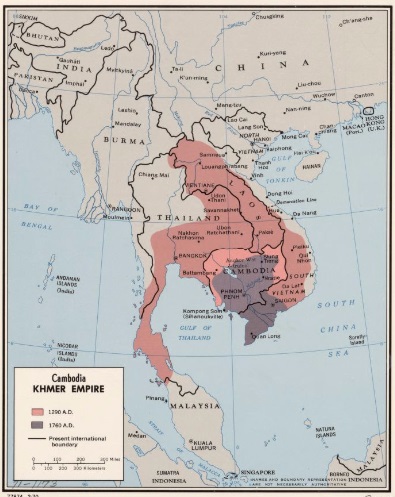

The Khmer Empire was remarkably prosperous, as its territory bordered Myanmar, near Chinese, and Champa (Champa country, but now Vietnam territory).

After the era of expansion was over, Khmer rulers tended to fight one another for power. Many sought helps from the other countries, requiting them with part of the territory and domestic products. Consequently, all what is left is 181,035 square kilometers of land, and countless rulers have been jailed, tortured or even killed by enemies.

“Khmer Rulers have tended to fight and seize power from one another since the ancient time,” said Sambo Manara, a professor of Cambodian history of Pannasastra University of Cambodia, giving three evidences to support his argument.

First– In Funan or Norkor Phnom Kingdom Era (550-630), during the reign of King Pvirakvarman I, there was an infamous war known as the Funan-Chenla war.

In 750, Chenla Kingdom was separated into the Land Chenla and the Water Chenla, each of which asked their enemies, such as Java and Cham, to help with the civil war and eventually lost the power to them during the Water Chenla part.

Second- During the prosperous Angkorian Era (1152-1177), the country ruled by King Suryavarman II fell into internal dispute, and again the king sought assistance from Champa. As a result, Angkor was controlled for four years and partly ruined by Chams until 1181.

Third – In 1470, King Sreyreachea won a war over Siem (Thailand), but when he came back, Prince Thormareachea refused the king back into to the country, creating another conflict. Meanwhile, Prince Srey Soriyasik created another separated territory for conflict as well, resulting in Cambodia being ruled simultaneously by three Kings´ conflicts. The dispute between the three kings was settled through the intervention from the King of Siam, Ayutthaya era.

While the three kings were in Ayutthaya city, King of Siam judged the case toed Prince Thormareachea, who had good relationship with Ayutthaya city, and imprisoned the other two, who were later tortured to death in Siem (Thailand).

In modern history, after its independence from French colonization in 9 November 1953, many claimed that Cambodia experienced rapid development, especially in fields such as education, sport, infrastructure, and rural development during the King Sihanouk-ruled The Sangkum Reastr Niyum. Unfortunately, it did not last long as the country fell into a civil war in the 1970s, where many references point the finger to the coup d’état by Gen. Lon Nol on 18 March, 1970.

No so few, however, argue that the so-called coup d’état was staged, claiming it was ordered down by King Sinhanouk himself to empower Gen. Lon Nol. This has been said to take place due to the downfall of national budget, and the large afflux of Vietnamese people into the country; King Sihanouk was not able to address these issues.

During the America-backed Lon Nol Regime (1970-1975), the society was characterized by atrocities and hostilities, such as continual armed violence and bombing in public (in fact: a bomb attack took place at central market in the town of Kampong Cham province two days after my parents wedding in early 1975 my mom told me); causing hundreds of deaths.

Meanwhile, Sihanouk wanted his power back, and called for the people to join the guerrilla (Maki forest, unknown name of this forest) force to fight against the Americans (Gen. Lon Nol’s regime). This guerrilla force had eventually become Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge, who evicted the people from the capital and cities to rural areas after having toppled the Lon Nol Government on 17 April, 1975.

Establishing a government known as Democratic Kampuchea, Khmer Rouge detained King Sihanouk and his family in the Royal Palace during 1975-1978 in after which he fled to China.

The Khmer Rouge supplies of weapons, equipment, and food originated from the support from China, and in return, Democratic Kampuchea sent most of their rice yield to China while its people were starving and killed. An estimated one and a half to three million people died during the years of the ruthless regime.

On 7 January, 1979, Vietnam-backed United Front for the National Salvation of Kampuchea defeated Khmer Rouge. While many said it was the salvation, many other have asserted it as the Vietnam’s “Invasion of Cambodia”.

After 10 years of occupation in Cambodia, Vietnam withdrew its troops from Cambodian after the peace process started in Jakarta in 1987. The Paris Peace Agreement in 23 October, 1991, resulted in the organization and monitoring of Cambodia´s national election by the United Nation Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) in 1993.

However, the real peace had not been found yet, which was contrast to what the rulers told the international community at the time. After the first election, the reconciliation and cooperation between the two ruling parties, FUNCINPEC and CPP turned into conflict and bias, eventually leading to the bloodshed battles and/or the coup d’Etat on 5th -6th July, 1997. At the time, there was no intervention from the UN or any other international body, apparently due to Cambodia itself claimed that it could be responsible for its own destiny.

Similar things still happens in the 5th term: atrocities, quarrels, feud, and harassment, and this is the result of competition between the ruling and the opposition.

The root cause of all these are the lack of long-term harmonization and unity in Cambodia. To get or maintain the power, the rulers or politicians have sought outside (foreigner[s]) help in the conflict with their regime / opponents in order to get power and then lost something (land or/and domestic products) in return, as proved by Cambodia’s history. Such an act contradicts to the concept of a democracy, in which the rulers work for the people rather than exploit them for power.

In such a country as Cambodia, both good and bad decisions are made by one single person. His/her subordinates, who often benefit from the decision, are fine with it but they tend to put all the blame on the leader. The cases of long term leaders of Ferdinand Marcos, the former dictator of the Philippines, and Sukarno Suharto, the former dictators of Indonesia are relevant examples.

Whereas the subordinate gets away with it, the critical aspect is when a dictator rules for so long that he or she has created a strong system which is difficult to change, even if the leader is changed. For example, Antasari Azhar, a former Chairman of Corruption Eradication Commission (2007- 2009), which has been fighting corruption over the rest of President Suharto’s subordination, was sentenced to 18 year in prison for alleged participation in the murder of a businessman. This was apparently a backlash from senior officials in the National Bank, court, military and the police, who have also been those repelled him by, a sentence of 18 years.

However, he is supposed to be released at the end of this September 2016 before term of sentence (The Jakarta Post).

In reality, the governing in Cambodian is not difficult than in Indonesia, where thousands of islands are located and where exist cultural, ethnic, and religious diversities. The problem lies on whether Cambodia has the commitment to do it.

Indonesia, which saw internal conflict during the liberation movement in the State of Aceh, accepted the reconciliation set out in the peace agreement between the Indonesian government and the Aceh movement at Helsinki, Finland, in 2005 and together signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) associated with some acceptable conditions. They ranged from autonomous state, law, and economic administration, amnesty, respect for human rights and monitoring missions.

Whereas Myanmar, a former military junta, is now accepting the reconciliation and peace-building, having gone through years of dictatorship in the past. Winning a landslide victory of election last year, Aung San Suu Kyi did not seek revenge from the ruthless general while Thein Sein, the former president, peacefully descend from presidency, leaving it to the elite in Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy. Then he briefly entered the monkhood and declared leaving politics upon his monkhood was over.

The core of the reconciliation between Suu Kyi and the military chief was the vow not to seek revenge, which led the peaceful power distribution, for the sake of the nation.

Meeting Thai prime minister last month, Suu Kyi called for the Myanmar migrant workers to “go back home”, as a leader and as a mother as well. Such act is the act of peace-building.

How about Cambodia? When will the top party leader seek the win-win policy for the good of the country? Could the use of dialogue be reused to find the real peace? By producing an amnesty law to not seek revenge on any leader who practices good and bad balance.

Last year, during a family dinner, which was held only once, the people were surprised to see both prime minister Hun Sen (CPP) and Sam Rainsy (CNRP) president got along so well together. It implies that the sought of revenge should put to its end. At that time, Hun Sen gave a clue to Sam Rainsy that if he loses power, please do not use the Khmer revenge slogan: “When it floods, Fish eat Ants and When it has dried, Ants eat Fish!”

When Hun Sen raised this slogan, it seems he wants a peace process with Sam Rainsy. This speaking however is not useful unless a formulation of an amnesty law or a MoU between both leaders to not seek revenge but think of the peaceful nation. Cambodia should learn from the good peace processes from Myanmar and Indonesia and apply the lesson on their own case. No doctor or even magician, otherwise, could save the country.

Tong Soprach is a social-affairs columnist for the Post’s Khmer edition.

Comments: [email protected]